It's the scientific equivalent of finding a needle in a haystack.

When people began falling seriously ill with listeria infections across south-east Queensland, NSW and Victoria in mid-August, a crack team of investigators set out to track down the source of the bacteria.

Dozens of people across the Queensland public health sector were involved – from laboratory scientists to environmental health officers, epidemiologists, infected patients, and their families – with every skill and piece of information proving vital to find and arrest a bacterial criminal.

Time was critical for these highly-trained food sleuths, who approach the job with all the zeal of police detectives pursuing a killer.

While most people will not be severely affected when they consume listeria-contaminated food, a minority – such as the elderly, those with suppressed immune systems or chronic medical conditions, and unborn babies – can become extremely sick, and potentially die.

Pregnant women can have miscarriages, premature deliveries, and stillbirths. People can also develop septicaemia, a severe infection of the bloodstream, or meningitis, a dangerous inflammation of the brain.

The sooner the source of the foodborne listeria can be found, the sooner the outbreak can be stopped. But listeria bacteria are among the most elusive of infectious offenders.

The process of tracking bacteria DNA

The incubation period – the time from becoming infected with the bacteria, to the onset of symptoms — varies from a few days to a couple of months, complicating the hunt for the source.

And the list of foods it commonly hides out in is very broad, including cold meats, prepared salads, cut fruit, soft cheeses, soft-serve ice-cream, and shellfish.

Nine cases have been connected so far to the cluster – five in Queensland, three in NSW and one in Victoria.

Genomic test results uploaded to a national database shows all nine patients are linked, with the culprit – listeria bacteria – sharing the same DNA fingerprints.

The five Queensland cases have connections to two public hospitals; four with the Mater and one with Redcliffe.

As late as a few hours before the state's chief health officer, John Gerrard, announced the origins of the cluster – a batch of shredded chicken sold commercially in 2kg bags by M and J Chickens in Marrickville, Sydney – his interstate counterparts were telling him: "You'll never find the source".

"This result is a testament to the extraordinary professional work of our public health teams and laboratory scientists," Dr Gerrard said.

"This is an extraordinary piece of detective work."

It would take the combined efforts of Queensland Health's communicable diseases branch, Forensic and Scientific Services and the Metro South public health unit all working in unison to solve the outbreak within about four weeks.

How did they crack the case?

Metro South environmental health officer Rona Roustom interviewed all five Queensland cases – one at the bedside – and their families, trying to drill down on where they had eaten and what they had consumed in the lead-up to becoming unwell.

"Environmental health officers are generally tenacious in nature," she said of her role.

"It's a very sensitive environment to work under. These people are very unwell. It's difficult for them to remember what they've consumed."

With four cases linked to the Mater, the hospital food menu became a focus of the investigation.

"The fact that they were in the Mater was like a bell ringing," she said.

"We narrowed it down to several foods.

"When you know you're close … that encourages you to get into work quickly. It's rewarding to be able to find the source and stop it from spreading."

Consultant epidemiologist Russell Stafford, who divides his time between Queensland Health and OzFoodNet — the national foodborne disease surveillance body — said the sunshine state recorded about 10 to 15 cases of listeriosis a year.

Epidemiologists analyse disease data to track down and eliminate the source of an infection.

Dr Stafford said having a cluster connected to hospital food raised "alarm bells", particularly given invasive listeria infections had a death rate of about 25 per cent.

"The longer an investigation goes on, there's more and more cases," he said.

"The sooner you can identify a source and put good control measures in place, the sooner you stop cases in the community.

"A lot of brainstorming goes on. People are definitely dedicated to their jobs."

Using information from Ms Roustom's interviews and hospital records, Dr Stafford was able to target potential food sources for the listeria.

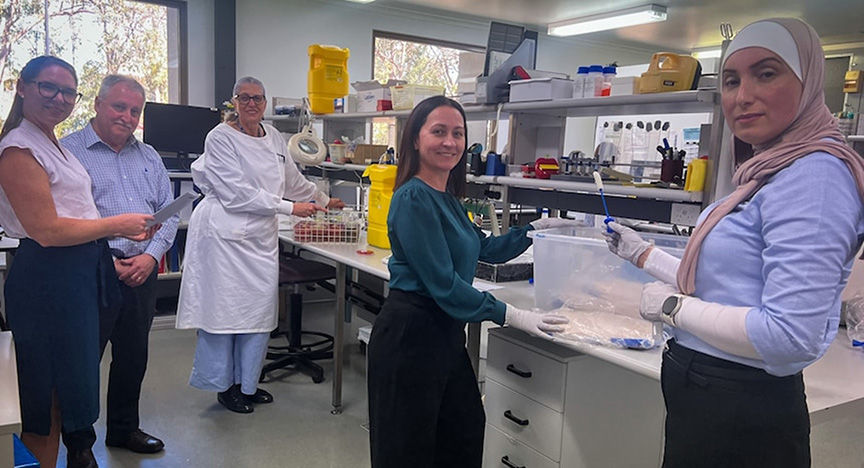

Samples were then collected and sent for testing to Queensland Health's Forensic and Scientific Services (FSS) laboratories at Coopers Plains, in Brisbane's south.

FSS chief scientist of public health microbiology Amy Jennison said notifiable bacteria and other concerning pathogens from Queensland cases, except tuberculosis, were sent to the Coopers Plains laboratories for investigation.

"We're very passionate," Dr Jennison said.

"The sooner we can find a pathogen, the sooner foods are recalled off the market, or the sooner a kitchen is deep cleaned and there is less cases of a particular disease.

"We always feel like the clock's ticking. We literally throw everything at it.

"This is one of those areas where we are really proud of ourselves because we do find the needles in the haystack.

"If you do public health well, no-one knows you're there because you are literally stopping things from happening."

Outbreak trends

Dr Jennison said the number of investigations into foodborne pathogens in Queensland varied every year. She said outbreaks dropped off during the early years of the COVID-19 pandemic.

"People weren't cooking food in large quantities, doing big dinner parties," Dr Jennison explained.

"There were less people eating out."

Food poisoning caused by bacteria, such as salmonella, are more common in summer.

In 2015, Queensland suffered through what the scientists dub the "summer of salmonella", but the reasons behind the jump in cases compared to other years remain elusive.

"It was a warm summer, and we were able to identify some of the transmission patterns that were occurring with some of the food," Dr Jennison said.

"But overall, we don't know why there was such a peak all at once."

FSS food microbiologist Trudy Graham has been involved in investigating foodborne disease outbreaks for almost three decades.

When she detected listeria on agar plates working through a weekend recently, it was a eureka moment for the three-state cluster, suggesting the shredded chicken was the source.

"There's a skip in our step when we find it," Ms Graham said.

"That makes it worthwhile, coming to work every day, to find that one in amongst many."

She sent samples off to the FSS genomics team to back her findings with DNA fingerprinting and, a few hours later, Dr Gerrard fronted a news conference to warn the public about the contaminated shredded chicken.